Jonathan Holmes is a Fairfax columnist and former presenter of Media Watch.

For better or for worse, most Australians are not Charlie Hebdo

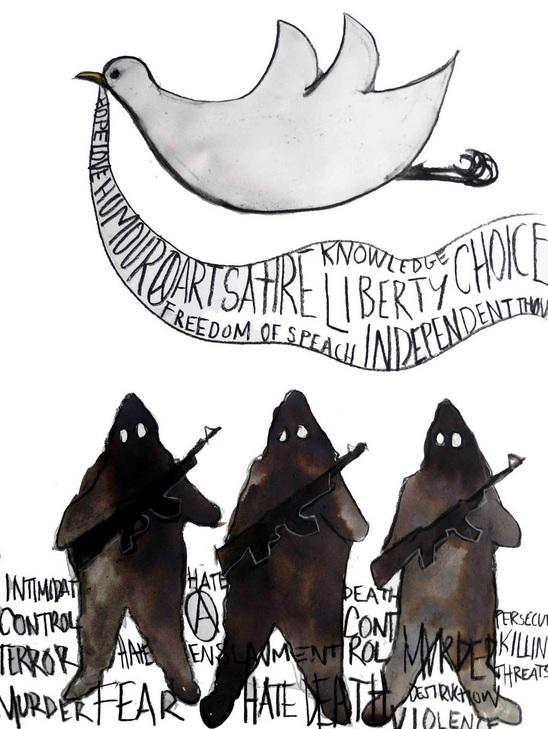

Some issues aren’t complicated. They are simple black and white. The murder of 17 French innocents, 10 of them simply for being involved in a publication that ridiculed Islam, is an outrage. It should be condemned. Je suis Charlie.

But is it so simple? The Andrew Bolt doesn’t think so. We Australians are NOT , he declares, because we don’t have the guts: “This fearless magazine dared to mock Islam in the way the left routinely mocks Christianity. Unlike much of our ruling class, it refused to sell out our freedom to speak.”

Bolt omits to point out that the murdered editors and cartoonists of were quintessential lefties themselves, who mocked and lampooned the French state and the Roman church with every bit as much gusto as they ridiculed Islam.

Attorney-General George Brandis.

But Bolt is certainly right that most Australians have shown quite recently that they don’t share Charlie Hebdo’s uncompromising views on freedom of speech.

It is unlawful in Australia to do anything in public – including the publishing of articles and cartoons – that is “reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or group”, if “the act is done because of the race, colour, or national or ethnic origin” of that person or group.

There are exemptions to section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act for the publication of fair comment on a matter of public interest, published “reasonably and in good faith”. But as Bolt discovered when Justice Mordecai Bromberg found him in breach of the act, whether an article is covered by that exemption depends not just on its accuracy, but on whether “… (in)sufficient care and diligence was taken to minimise the offence, insult, humiliation and intimidation suffered by the people likely to be affected …”

Bolt had not taken enough care, Justice Bromberg found, and not just because he had been inexcusably sloppy with his facts. “The derisive tone, the provocative and inflammatory language and the inclusion of gratuitous asides” in the articles complained of satisfied him that “Mr Bolt’s conduct lacked objective good faith”.

But I was one of those who agreed with Bolt that to make it unlawful merely to offend someone, on any grounds, is an assault on freedom of speech. I found Justice Bromberg’s judgment disturbing, and initially I supported the Abbott government’s determination to revise the act.

When Attorney-General George Brandis published his proposed revision, I changed my mind – it seemed to me that it went absurdly far in the opposite direction. (By contrast, I have no problem with the much simpler bill on the table, sponsored by Senator Bob Day and others.)

But most submissions on the government’s draft bill went further. Any revision to the act was opposed by almost every influential ethnic group; every lawyers’ organisation in the land; the entire human rights and social welfare establishment; and by Jewish, Christian and Muslim organisations. Seldom has a proposed legislative reform met such universal condemnation.

In the face of that chorus of disapprobation, and to Bolt’s disgust, the government backed down, and the act stands.

Now, of course, the federal Racial Discrimination Act does not apply to acts that concern a person’s religion – though the Victorian Racial and Religious Tolerance Act does.

Nevertheless, the very Australians who are most likely to be out on the streets today with their “Je suis Charlie” placards made it clear less than a year ago that in their view, at least so far as race is concerned, publications should not be free to give offence or to insult.

Let’s be clear: Charlie Hebdo set out, every week, with the greatest deliberation, to offend and insult all kinds of people, and especially in recent years the followers of Islam, whether fundamentalist or not.

Look at some of the magazine’s recent covers: An Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood protester in a hail of gunfire crying “The Koran is shit – it doesn’t stop bullets”; a full-on homosexual kiss between a Charlie cartoonist and a Muslim sheik with the ironic headline “Love is stronger than hate”; a naked woman with a niqab thrust up her backside.

Most of those who were so outraged by Bolt’s columns about fair-skinned Aboriginal people, and supported the use of the law against him, would find themselves equally appalled by much of Charlie Hebdo’s output. Even though the late Stephane Charbonnier, the magazine’s editor, inhabited the opposite end of the political spectrum, he shared Bolt’s determination to shock the chattering classes.

But whereas Bolt is an unashamed supporter of the Abbott government, Charlie Hebdo mocks all governments. If it were published in Melbourne rather than Paris, the magazine would be scathing about Australia’s new anti-terrorist laws, under which the government can guard all of its secrets from scrutiny and threaten any who reveal them with five years in prison, but we can keep none of ours from the government.

Yet the new laws have been greeted with tepid acceptance by most Australians. In protesting their over-reach, the media have been largely on their own. In this respect, too, nous ne sommes pas Charlie.

Perhaps that’s not surprising, when so many commentators are prepared to wind up the scary rhetoric. “A de facto world war is under way, and it has everything to do with Islam,” declared Fairfax’s Paul Sheehan on Monday.

That the murder of Charlie Hebdo’s staff was a hideous crime is beyond debate. It should be treated as such. But talk of world war brings with it a grave risk: that it will legitimise the remorseless encroachment by government on our liberties.

The enemy of my enemy is my friend, the saying goes. But the enemies of Islamic fundamentalism are not necessarily the friends of free speech.

For better or for worse, most Australians ne sont pas Charlie. It’s not such a black and white issue, after all.